Food Security: Key Dimensions of the Social Determinant of Health

Food security can affect overall patient well-being, plus diet-related chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

Source: Getty Images

- Food security is perhaps one of the most commonly discussed social determinants of health, with the medical and public health industries standing poised to address it.

According to Healthy People 2030, food insecurity is “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food.”

Food insecurity has two different levels of severity, per the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). Low food insecurity indicates limited access to healthy, nutritious, or high-quality food. Low food insecurity is not always associated with hunger.

High food insecurity, however, is usually associated with hunger. High food insecurity is associated with low food intake and disrupted eating patterns, the USDA says.

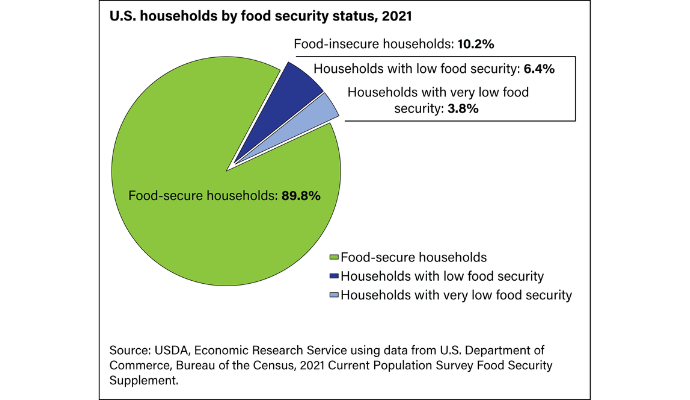

Nearly 118 million Americans were food insecure throughout 2021, USDA figures show. Specifically, they aren’t eating enough food labeled nutritious and are consuming too much food that could have adverse health consequences.

Source: USDA

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), fewer than 1 in 10 adolescents and adults eat enough fruits and vegetables, but nearly 9 in 10 consume too much sodium.

Considering the impact food access and security can have on health and well-being—plus the huge price tag (the CDC puts the cost of obesity care at around $173 billion)—healthcare entities have turned their attention to the issue.

The good news is, food insecurity has a somewhat simple answer: connect people to affordable, nutritious food options. That’s what has made food security a good starting point for organizations working to mitigate social determinants of health.

Still, the nuances of food insecurity are varied, and ensuring good health outcomes is not as simple as getting people to the right grocery store. Below, we’ll discuss the ins and outs of food insecurity and where the healthcare industry is in addressing it.

Clinical outcomes tied to food security

Food security is perhaps an obvious social determinant of health because of the myriad of illnesses that are diet-related. Although general health and well-being are influenced by access to food and nutritious food choices, the CDC says that the following disease states are specifically related to diet:

- Overweight and obesity

- Heart disease and stroke

- Diabetes

- Cancer

“Good nutrition is essential to keeping current and future generations healthy across the lifespan,” CDC says on its website. “A healthy diet helps children grow and develop properly and reduces their risk of chronic diseases. Adults who eat a healthy diet live longer and have a lower risk of obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. Healthy eating can help people with chronic diseases manage these conditions and avoid complications.”

The clinical impacts of food insecurity are many, ranging from out-of-control blood sugar for patients with diabetes to exacerbated high blood pressure. Healthcare providers and their patients know this, which is why eating a nutritious diet filled with whole grains, fruits, and vegetables is a common recommendation from clinicians.

But actually obtaining that nutritious food can be difficult, leaving many patients unable to follow those recommended healthy behaviors.

Causes of food insecurity: cost, food swamps, food deserts

As noted above, most patients know that a healthy diet will help them achieve better outcomes. But in terms of food insecurity, access can be difficult. Food insecurity is usually driven by three main barriers:

- Cost of groceries

- Dearth of healthy food options (food deserts)

- Oversaturation of unhealthy food options (food swamps)

Cost

First, cost influences food security because it determines how much and what kind of groceries an individual purchases for themselves or their family.

More nutritious food also happens to be more expensive, limiting the options some low-income families might have when shopping for food. In the same vein, less nutritious options like food from convenience stores and fast-food establishments tend to be less costly, proving a more financially sound option for some people.

March 2023 data from the Urban Institute drew a line between food affordability, nutritional value, and obesity. Places with higher rates of obesity also had a higher density of low-cost food retailers, like dollar stores, which also happen to sell less nutritious foods.

Cost is a looming factor in health and well-being, as 2022 and 2023’s trends of inflation are making it harder for people to afford their groceries. September 2022 data from the University of Michigan showed that within the previous year, food costs rose 13 percent, leaving a third of older adults in a bind for buying nutritious meals.

Food deserts

Food deserts are places in which there is a lower density of establishments at which people can conveniently buy food, particularly nutritious food.

An article from the Annie E. Casey Foundation says that food deserts are more common in places with lower populations, more vacant or abandoned homes, and places where other social determinants of health (educational attainment, income, and employment) are common.

Food deserts naturally impede food security because they can mean people are not able to buy their groceries. Individuals living in food deserts may not have as much to eat, and because buying groceries is not convenient, they may opt for foods with more preservatives, as opposed to fresh foods, to make the haul last longer.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation article stated that food deserts crop up because of transportation barriers and the prevalence of other food sources, like convenience stores and dollar stores. Moreover, food deserts may arise because grocery stores do not deem a certain area a good investment for building.

Notably, food deserts are more common in mostly-Black neighborhoods and regions.

Food swamps

Food swamps are different from food deserts because they are not characterized by a lack of overall food options; they are characterized by a lack of healthy food options. These are areas that are oversaturated with food establishments and retailers that sell food that is not regarded as nutritious. These food options tend to be lower cost, and many food swamps are concentrated in low-income areas home to populations of color.

While food swamps may not necessarily be linked to hunger, they are linked to poor outcomes in chronic illnesses that are related to diet. That Urban Institute data, for example, showed that places with food establishments less likely to sell nutritious food overlapped with places with high rates of obesity.

And according to researchers at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, living in a food swamp can also increase the odds of stroke among individuals ages 50 and older.

Experts have argued that diluting food swamps will require policy action, particularly capping the number of establishments unlikely to sell nutritious foods in a given area.

Culture is a key caveat

It should also be noted that there is also a key cultural caveat influencing access to nutritious foods. The “healthy diet” recommended in most doctor’s offices has been shaped by western influences and doesn’t always account for the foods and traditions embraced in other cultures.

A patient with diabetes may not follow the low-carb diet her doctor recommended because she is of Mexican heritage and rice is a staple to her cultural preferences. It is incumbent upon healthcare providers to practice cultural humility in these instances and shape healthy diet recommendations that are realistic to a patient’s culture.

Food security interventions

Food security is one of the top common social determinants of health being addressed at the health system and federal levels. That is because there is a relatively clear answer for the food security problem: set up mechanisms by which folks can access affordable and nutritious groceries.

Said otherwise, healthcare experts know the answer to their food insecurity problem; however, getting to that solution can be complicated.

Perhaps the most notable solutions for food insecurity are SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) and WIC (Women, Infants, and Children).

According to the USDA, SNAP helps low-income families buy groceries. SNAP is run by state agencies, which determine eligibility. Eligibility usually depends on family income.

WIC “provides federal grants to states for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age 5 who are found to be at nutritional risk,” the USDA says on its website.

These programs work, studies have shown, with a report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) outlining that WIC, in particular, fosters healthier babies, increases the odds of infant immunization, and boosts child mental development. WIC has also had a spillover effect, increasing the amount of nutritious food consumed in low-income neighborhoods, regardless of whether an individual is a WIC beneficiary.

Healthcare organizations have likewise targeted food security and access. Food is typically one of the key social determinants of health assessed during SDOH screening, primarily because healthcare organizations are able to refer patients to resources to address food security.

Via community health partnerships, hospital-sponsored food vouchers, and more unique programs like rooftop gardens, healthcare organizations have made their own overtures to connect patients in need with nutritious food.

Hospital-sponsored initiatives are particularly impactful for low-income people who do not qualify for SNAP or WIC. Some hospitals are even helping patients enroll in SNAP if they qualify but are not already in the program.

But efforts from both public health and government organizations and the ones from hospitals can only extend so far. There are some gaps in SNAP enrollment, with many people eligible for the program not getting enrolled, according to a 2021 study. For some families who are enrolled in SNAP, the benefits still are not enough to close food security gaps.

In September of 2022, the White House convened a weeklong conference on hunger, issuing its five-point plan to address hunger, nutrition, and health. Central to that effort is expanding SNAP, the White House said, as well as creating access to medically tailored meals and setting up incentives for the purchase of nutritious foods.

The White House acknowledged that its goals need Congressional support, but the conference served as an important symbolic overture to ensure more attention is paid to food security as a leading social determinant of health.