“First Do No Harm:” Combatting Black Maternal Health Disparities

Decades of health inequities have led to stark, and worsening, black maternal health disparities.

Source: Getty Images

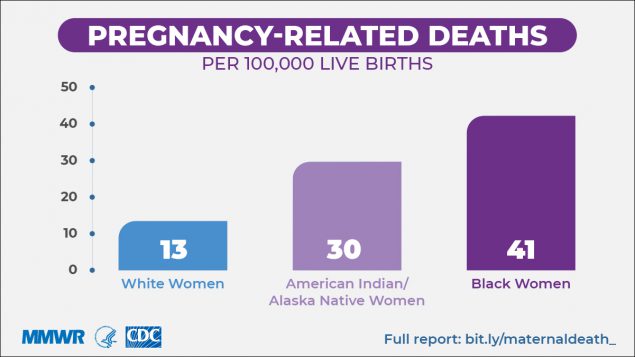

- “First do no harm.” That is the basis of all US medicine, and yet for certain populations, it’s not always true. Case in point: Black maternal health disparities. Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native mothers are two- to three-times more likely to die from childbirth than their White peers.

Over the past two decades, global maternal mortality has worked its way downward, seeing a 34 percent drop between 2000 and 2017. But pregnant people in the US — who for the purposes of this article will be called pregnant women — haven’t seen those kinds of improvements.

The CDC reports that severe maternal morbidity (SMM), or life-threatening pregnancy-related complications, affects 50,000 women per year as of 2014, the most recent year for which the agency has national data.

Source: Centers for Disease Control & Prevention

That’s a nearly 200 percent jump in about two decades; in 1993, the SMM rate was 49.5 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations and in 2014 it was 144 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations.

But SMM and other complications are hurting racial and ethnic minority populations more.

In September 2019, the CDC reported that even in the states with the lowest pregnancy-related mortality ratios (PRMRs) and among women with high educational attainment, Black and AI/AN maternal health disparities still persisted.

And these issues are plaguing the babies, too. In 2016, infant mortality, defined as death before the child’s first birthday, for Black babies was 11.4 per 1,000 live births. For non-Hispanic White babies, it was 4.9 per 1,000 live births.

“It is a public health crisis,” said Lavdena Orr, MD, FAAP, market chief medical officer for AmeriHealth Caritas District of Columbia. “We all should be alarmed by this and we all should be working together to reduce the rates of deaths among women of color and infants of color.”

But the challenge is, Black maternal health disparities are so pervasive that they permeate nearly every step of the healthcare system. The causes of Black maternal health disparities are not limited to one area of medicine, but instead they stem from shortcomings across the care continuum.

Black women are coming into pregnancy sicker than their White peers because they have faced years of structural inequities that have made it harder for them to stay healthy. Black women are more likely to experience the social determinants of health than their white peers.

And in the doctor’s office, the specter of implicit bias and the United States’ grotesque history surrounding Black female reproductive health and eugenics has caused lasting damage to the patient-provider relationship. Ultimately, this impacts the level of care quality during pregnancy and post-partum.

All of this takes place among the backdrop of a health insurance industry that is not always workable for pregnant women of color.

As the healthcare industry unequivocally recognizes racism as a public health issue, it can no longer ignore the problem of Black maternal health disparities simply because of its enormity.

By committing to create social programs that support health equity, working to dismantle implicit bias in the exam room, and building a healthcare payer infrastructure that is intuitive and navigable for all patients — in short, to “do no harm” — medicine can begin its journey to closing Black maternal health disparities.

How health inequities have plagued Black maternal healthcare

Notably, a large driver of Black maternal health disparities are the disparities in other comorbidity rates among Black women before they even become pregnant. Black women are more likely to have a high-risk pregnancy because they are more likely to have some sort of a chronic illness to begin with.

“Many of the women have pre-existing medical conditions such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes,” Orr explained.

The literature corroborates that. The CDC reports that obesity is more prevalent among Black people than White, as is the case for hypertension and diabetes.

And that’s not because White people are better at taking care of themselves or are less predisposed to getting sick. Instead, Black women have faced structural inequities that have limited their ability to access primary care, or at least access it in a meaningful way. This has led to poor early detection of chronic illness and limited chronic disease management, according to experts.

“Most of those conditions can be prevented by making sure that women engage in primary care, have access to primary care. That is important,” Orr stated.

But the fact of the matter is women of color are far less likely to have a reliable source of primary care than their White peers. A 2014 assessment published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine found that White people are more likely to have a usual source of care, which often denotes primary care, than their Black and Hispanic peers.

Black people were also more likely to say they receive their primary care from a facility or hospital in general, as opposed to having a specific medical professional as their usual source of care.

It’s in that closer look at Black women’s access to primary care that the domino effect contributing to Black maternal health disparities finally appears. Black women are more likely to experience social determinants of health, which not only serve as upstream triggers for certain chronic illnesses, but also make it harder for Black women to engage with primary and pre-natal care.

Black women also face implicit bias, which makes it harder for them to trust that the healthcare system writ large will work in their best interests and in many cases can influence the interactions they have with their medical providers.

All of these issues adversely impact the way Black women interact with primary care and pre-natal care, eventually creating crushing Black maternal health disparities.

Breaking Down Causes of Maternal Mortality:

The five leading causes of maternal mortality include hemorrhage, cardiovascular and coronary conditions, infection, cardiomyopathy, and embolism, according to a report from Review to Action, which looked at maternal mortality in nine states. But when broken down by race, some disparities appear.

For Black women, the leading causes of maternal mortality include:

• Cardiomyopathy (14 percent of deaths)

• Cardiovascular and coronary conditions (12.8 percent of deaths)

• Preeclampsia and eclampsia (11.6 percent of deaths

• Hemorrhage (10.5 percent of deaths

• Embolism (9.3 percent of deaths)

These conditions account for 58.1 percent of all Black maternal mortality, suggesting that Black women face a broader array of medical conditions that could cause maternal mortality.

Meanwhile, for White women, the leading causes of maternal mortality include:

• Cardiovascular and coronary conditions (15.5 percent of deaths)

• Hemorrhage (14.4 percent of deaths)

• Infection (13.4 percent of deaths)

• Mental health conditions (11.3 percent of deaths

• Cardiomyopathy (10.3 percent of deaths)

These causes account for 64.9 percent of all White maternal mortality, suggesting that a smaller variety of medical conditions lead to maternal mortality for non-Hispanic White women.

Social determinants of health erode Black women’s health

It is impossible to speak of Black women’s health without discussing the social determinants of health, or the social factors that affect a patient’s ability to obtain wellness.

While it is challenging to measure racial disparities in how many patients experience the social determinants of health writ large, the evidence is unequivocal that Black patients experience specific social determinants of health more often than their White peers.

Housing security, for example, is a bigger problem for Black women than for White women, according to Stacy Millett, the director for the Health Impact Project at the Pew Charitable Trusts. The Health Impact Project, which Pew runs in partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, investigates how social factors influence health outcomes, like Black maternal health disparities.

“In general, if you don't have a home, your life expectancy is anywhere from 20, 25, maybe even 30 years less than a person who is housed,” Millett told PatientEngagementHIT. “And when you think about being a pregnant woman who's un-housed, that is particularly deleterious. You're putting yourself at risk for low-term birth or early birth, pre-term birth, and other really horrific health consequences.”

According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, 40 percent of individuals who are homeless are Black, despite Black people comprising only 13 percent of the total US population. Factors like poverty, the history and current state of housing and rental discrimination, incarceration, and access to mental health treatment all contribute to this disparity, the Alliance said.

And like Millett noted, housing insecurity has long been known to exacerbate health conditions in all patients, pregnancy and potential pre-existing conditions included. These stressors can be bad for pregnant women and babies, who could see low birth weight as the result of a housing insecure pregnancy, according to research in the Journal of Urban Health.

“Housing is almost a prescription for health and particularly as we look at pregnant women or people without homes,” Millett said. “This is a really important issue, so hospitals should plug themselves into the network where community organizations are and go out and ask questions and listen authentically when perhaps there's an opportunity.”

Transportation, too, is an issue. A 2017 biennial report from the Boston Public Health Commission found that Black women are more likely to rely on public transportation and resultantly see transportation challenges when accessing healthcare.

Fifty percent of Black women in the Boston area have been late to or missed a medical appointment because of public transit, compared to 45 percent of White women who said the same.

That’s likely because Black women are more likely to rely on public transit in the Boston area. Fifty-six percent said they regularly use the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) to get to medical appointments, compared to 38 percent of White women.

About equal proportions of Black and White women said it took them more than 30 minutes to get to a medical appointment, the report concedes, but the MBTA is infamously unreliable, which could deter some Black women from accessing care in the first place in order to avoid the frustration of public transit.

Again, hospitals are making some progress in this area, Millett reported.

“There are some hospitals around the country that have started to invest in providing dollars to get women to hospitals for appointments or just the care clinics,” she said. “That's another example that might seem like a small thing, but it's actually a really big thing to be able to get someone to a hospital if you're about to deliver a baby.”

As a Medicaid managed care organization, AmeriHealth Caritas is also working to address the transportation issue for pregnant women, especially Black women.

“We provide transportation free of charge to all of our enrollees, but in particular for our pregnant moms because in one section of this city there are very few OB providers,” Orr said. “There are no maternal-fetal health specialists in one section of the city, so anyone who is high risk — and many moms are because they've had high-risk pregnancies before or they have pre-existing medical conditions — they have to take transportation across town. If we don't provide the transportation, they have to take three buses to get to a maternal-fetal specialist.”

Although there are many provider and payer organizations beginning to do the work of addressing social determinants of health for Black women, accessing those social services benefits is not always easy.

Some services for medical transportation might be available, but bureaucratic barriers coupled with low patient activation could still leave some pregnant women without. Part of the process of setting up a strong social services benefits program is for the payer or the provider to help the patient navigate it.

All of this comes with the added issue that discrimination itself is its own social determinant of health, as espoused by Healthy People 2020. Discrimination can be an added stressor that ultimately affects health outcomes, some research is beginning to reveal.

Outside of those reduced outcomes, decades of discrimination can seep into the exam room itself. Implicit bias is a hindrance to the strong patient-provider relationship that is necessary to help the patient receive optimal pre-natal and post-partum care and navigate the healthcare landscape.

Unpacking implicit bias in the patient-provider relationship

To be clear, it is extremely uncommon for a clinician to be explicitly racist, experts agree.

“It is probably the rare clinician who wakes up in the morning and figures, ‘I'm going to mistreat some of my patients today,’” said Janice Huckaby, MD, chief medical officer of Maternal Child Health at Optum.

But as humans, clinicians all have implicit bias to some degree, Hackaby stated.

“Some of it may be born of just encountering people who look or speak or act differently than we do, some of it may be because we have family environments that have encouraged a certain way of thinking, some of us may have picked up perspectives from education or things we read or the internet for that matter.”

“But the scary thing about implicit bias is that oftentimes people are unaware that it's shaping some of their reactions,” Huckaby stated.

Huckaby has heard implicit bias show itself in conversations with doctors treating Medicaid patients, referring to patients as “Medicaid Queens” or using other language that can suggest the patient is someone who is “less than.”

When thinking about race, it’s often a lot more subtle than that, Huckaby pointed out, and not always ill-intentioned, although its impact is still harmful. Most providers truly believe they are doing what is best for their patients and working their hardest to drive a positive health outcome.

But still, subconscious notions about certain demographic groups can shape patient-provider communication and potentially not for the better.

“For instance, a physician might go in and explain what was going on one way to a patient who looked and spoke like he did, and might cut short a detailed explanation to someone else who he deemed different or less able to understand or less educated,” Huckaby explained. “The dangers with implicit bias are that these interactions leave us talking at each other, instead of talking with each other.”

What can result can be disastrous for health and wellness. Patients can pick up on implicit bias at play in a healthcare encounter and that, coupled again with the dark history American medicine has with Black women’s reproductive health, can put a brick wall between patient trust and medical institutions.

And that could mean the patient doesn’t show up for pre-natal or post-partum care, or primary care in between pregnancies. These patients aren’t being non-complaint; they just don’t feel welcome or understood. Without those regular check-ins, certain medical red flags may become insurmountable problems that contribute to PRMRs or SMM.

For example, according to Orr, implicit bias may affect whether a pregnant patient gets the referral to a pregnancy specialist that she needs.

“The other component of this is for general practitioners and general OB to understand when to refer a pregnant mom because she is high-risk. They cannot let their unconscious bias or cultural competency issues interfere with referring a woman of color to a maternal-fetal specialist,” Orr explained. “Not deciding that, ‘oh well she can't afford it or she won't go,’ but referring that mom so she gets the best care for the high-risk condition that she may have.”

The good news is that with hard work and education, implicit bias can be recognized, which can help providers course-correct throughout a healthcare encounter. But for many clinicians, starting with the basics has been the hardest.

“A lot of implicit bias training could just start with the awareness that we all have some kind of implicit bias for many, many different reasons from how we grew up, what we're supposed to do,” Millett said. “But it's about how we behave and what we can do.”

And as the nation faces a racial reckoning, many in the medical community stand poised to do the work of unlearning their subconscious tendencies.

Zooming in on the payer landscape

All of this is happening inside a labyrinth of a healthcare payer industry. Health insurance and payer coverage are challenging for nearly all patients. After all, nearly one-fifth of Americans rely on some sort of healthcare navigation to understand their insurance options. But according to Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, a managing director at Manatt, things get complicated for pregnant women because their benefits eligibility can change.

“One of the biggest issues is really the focus is continuity of coverage,” she said to PatientEngagementHIT. “Because if you think about what happens when you add another person to your family, your income changes automatically.”

If a pregnant woman makes $40,000 as a family, that will look different when she has her child and has a new number of people living in the household.

“Women may be transitioning between healthcare coverage at a very vulnerable time,” said Brooks-LaSure, who is a former policy official who helped work on the Affordable Care Act’s passage. “At a time when they are just getting their feet under them, having had a baby needing to make sure they're taking care of all of the things that they need to do, maybe transitioning back to work, all of those things.”

Specifically, patients need to know when they have to apply or reapply for coverage, because after having a baby a woman may no longer be eligible for Medicaid or certain subsidies and need to shop on the marketplaces for a different plan. Some states are setting up systems to notify women who fit into that category, while others are leveraging 1115 waivers to extend post-partum coverage, which gives women more time to transition health plans.

This is another area where healthcare navigators, who help patients understand and work the ins and outs of the healthcare and health payer space, are beneficial, Brooks-LaSure said.

“This is clearly an area where states can help make sure that the various groups that help people enroll in coverage today are funded and be aware of this issue,” she asserted

How Can Doulas Help?

Some industry leaders have been considering the use of doulas in maternity care as a strategy to address Black maternal health disparities, both Orr and Brooks-LaSure mentioned.

According to the American Pregnancy Association, “the doula is a professional trained in childbirth who provides emotional, physical, and educational support to a mother who is expecting, is experiencing labor, or has recently given birth,” the group says on its website. “Their purpose is to help women have a safe, memorable, and empowering birthing experience.”

Although the doula doesn’t actually deliver the baby or administer medicine, she can play a significant role in patient advocacy before, during, and after birth to ensure the patient is safe and healthy. Some Medicaid programs are beginning to add doulas to part of their care access offerings.

“New York is an example of a state that is trying to include doulas in the delivery of care,” Brooks-LaSure said. “A couple of other States also have these initiatives. These types of programs are trying to make sure that women have additional support at the time of delivery. One of the issues is making sure that doctors and nurses really understand the level of pain or problem that the mother may be experiencing. That can be a place where doulas provide help, but also after the baby is born.”

The health payer landscape also falls short for women during pregnancy, with fragmented care leaving a lot of women experiencing gaps in care and, consequently, outcomes.

“We need to look at the system of care that we provide our moms to make sure it is transferable, it is consistent, and that all of the support they need can be accessed from one central place,” Orr said.

Overcoming these challenges is going to require cross-sector and innovative strategies, Orr suggested. Community health partners will help keep patients connected to no-cost or affordable care, despite complex payer coverage issues. Setting a national standard for or assessment of maternal care could also provide a step forward.

Huckabee agreed, saying that as soon as leading healthcare players make the decision that they want to be a part of the solution, to “first do no harm,” it will spark a ripple effect.

“This isn't something to be legislated, and it isn't something that can be decreed,” Huckabee concluded. “It's going to be each individual, each organization trying to do better than they had before. That's the kind of commitment we'll need before we can see this tide turn.”